The introduction of a bill to repeal the Durbin Amendment has added more fuel to the fiery debate between the nation’s largest banks and retailers. But at least for now, it’s not going anywhere.

In 2017, CNBC noted that Republicans planned to drop a proposed repeal of the Durbin Amendment.

Additionally, financial and political publications have reported on the possibility of expanding provisions to cover credit cards, not just debit cards. In 2022, Forbes published a piece suggesting that expansion to credit cards is a bad idea and that Congress should have repealed the Durbin Amendment in 2017 when it had the chance.

Yet, with all of these discussions going on, many small businesses and consumers don’t even know what the Durbin Amendment is, not to mention the impact payment experts and economists claim it has supposedly had. What would Durbin Amendment repeal mean for businesses?

- News and Updates

- Two Complicated Sides of the Durbin Debate Coin

- The Durbin Amendment for the Layman

- The Battle over the Durbin Amendment Begins

- Arguments to Repeal Durbin

- Arguments to Uphold Durbin

- Big Picture: Durbin Missed “Main Street”

- Debit Network Routing: A Tough Choice

- Arguments to Repeal Durbin: Take Two

- Arguments to Uphold Durbin: Take Two

- My Two Cents

- News and Updates

News and Updates

In May 2017, the House Financial Services Committee voted to send the Financial CHOICE Act to the House of Representatives for futher consideration. The Financial CHOICE Act, introduced by Texas’ Jeb Hensarling, would repeal significant portions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which includes the Durbin Amendment. Among other things, the Financial CHOICE Act seeks to alter the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau – including the ability to make the CFPB director dismissable by the President – and repeal the Durbin Amendment capping debit card interchange.

May 25, 2017 – Multiple news organizations report that Republicans will drop an effort to repeal the Durbin Amendment of the Dodd-Frank Act. US News and World Report quotes House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling: “I’ve said before that repeal of the Durbin amendment was the most contentious part of the bill among Republicans. I believe it belongs in the Financial CHOICE Act, but I recognize and respect that many members of Congress feel differently.”

The Financial CHOICE Act, a bill intended to roll back provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act, is still being considered and could potentially affect watchdog organization Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. While the Durbin Amendment could come up again, it appears that for the time being the Durbin Amendment will remain in place.

The Two Very Complicated Sides to the Durbin Debate Coin

On one side are the mega-banks and their lobbies that want to repeal the Durbin Amendment because it cuts into bankcard revenue and forces the weight of the quest for profits on to the shoulders of the economically disadvantaged consumer. This leads to rising bank fees and an increase in the so-called unbanked population.

And on the other side of the debate are large businesses comprised of mostly retailers and interest groups that want to uphold the amendment because, among other things, it has the potential to reduce credit card processing fees through pricing caps and transaction routing for businesses that understand enough about interchange to actually reap the benefits.

Not surprisingly, this group does not include many – I venture to say most – small to medium-sized businesses that are still very much in the dark about processing costs in general, not to mention the complexities of the Durbin Amendment impact on debit interchange and network routing.

The general position of the two sides is where any semblance of simplicity around the Durbin debate ends. And what impact the amendment has had, and whether that impact is seen as good or bad, depends very much on your vantage point.

The Durbin Amendment for the Layman

If you’re like most people that have been impacted, perhaps unwittingly, for better or worse by the Durbin Amendment, you’re not an expert on payment processing, or on economic theory – so you may not be completely clear on the details of the amendment.

To bring you up to snuff as painlessly as possible, I’ll provide a high level view by outlining the key points of it here.

The Durbin Amendment passed as part of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010. It has the following key components:

Debit Interchange Cap

The component of the Durbin Amendment that gets the most press is the cap it imposes on the interchange fee collected by a bank when a cardholder makes a purchase using a debit card issued by the bank.

Interchange is a ridiculously complex topic on its own, so I’m not going to delve too deeply into the details here, but the gist of it goes like this:

If I pay for lunch using my debit card, the restaurant indirectly pays my card-issuing bank a fee for accepting my debit card as payment. The fee collected by my bank is calculated as a percentage of the sale amount, plus a fixed transaction fee. I’ll give an example of pricing below.

Per the Durbin Amendment, the amount of the interchange fee collected by the bank differs depending on the size of the bank, or more accurately, by how much money the bank has. Large banks with tons of money fall under the Durbin cap, while small banks with less money do not.

Regulated Banks (large, tons of money)

So-called regulated banks, as they’re referred to post-Durbin, are large banks that have $10 billion or more in assets. Think of banks like Wells Fargo, Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase – basically, the banks taxpayers bailed out back in 2008.

The interchange fee that regulated banks can collect is capped by the Durbin Amendment at no more than 0.05% of a transaction amount, plus a flat $0.21 (plus an additional $0.01 for meeting fraud criteria) when its debit card is used to make a purchase.

Unregulated Banks (small, less money)

Unregulated banks, on the other hand, are those with $10 billion or less in assets — think of credit unions and local banks.

These so-called unregulated banks are not subject to the cap, so they’re free to collect prevailing interchange, which is what all banks were able to collect before the Durbin cap.

For example, the current interchange for a Visa-branded debit card is 0.80% of the transaction amount plus a flat $0.15 when the card is swiped, and 1.65% plus $0.15 when the card number is keyed-in or the card is used to make an online purchase.

A Quick but Important Digression: It’s Not a “Swipe Fee”

Especially when talking about the Durbin debate, people tend to refer to interchange fees as “swipe fees.” Doing so is erroneous at best, and misleading at worst. It confuses the facts for anyone trying to understand how credit card processing fees really work.

Regulated debit interchange is capped by the Durbin Amendment for all types of transactions, including those where a card is not actually swiped, such as an online purchase.

The term swipe fee is a dangerously oversimplified reference to interchange fees.

It’s not a “swipe fee.” It’s an interchange fee. And in fact, many interchange categories regulated by the Durbin Amendment don’t require a card to be swiped.

Unaffiliated Debit Network Routing

The second part of the Durbin Amendment that receives far less attention than the first, but is quite significant in its own right, is the debit network routing requirement meant to combat network exclusivity.

The network routing provision requires all card-issuing banks, regardless of size, to enable routing through at least two unaffiliated networks, and it blocks card networks from restricting which networks an issuer or business may select.

If you think that sounds confusing, you’re absolutely right. In my opinion, this provision receives far less attention than the interchange cap because it’s a lot harder to grasp and explain. But that doesn’t make it any less important or impactful.

So, what’s the point? Why does freedom to route debit transactions over unaffiliated networks matter to the average business?

The short answer is: To allow for lower cost through increased competition.

Before the Durbin routing provision went into effect on October 1, 2011, card networks and card-issuing banks selected debit networks based largely on which ones produced the greatest income. Businesses had no choice in the matter.

Additionally, many debit cards carried routing capabilities that were limited to directly or indirectly related networks. For example, a debit card may have utilized the Visa network for signature debit routing, and the Interlink network for PIN debit routing. Visa owns Interlink, so this created a routing scenario where competition was completely eliminated.

Debit transactions were largely routed through the network that produced the greatest interchange income – a cost that is eventually paid for by the businesses accepting debit cards as payment.

Requiring issuers to enable at least two unaffiliated networks, and allowing businesses to choose through which networks to route transactions is meant to open up competition among networks and to provide the opportunity for businesses to route transactions through the network with the lowest cost.

The Federal Reserve Board’s Compliance Guide to Small Entities is a good overview for those who would like to learn more about the network routing provision.

The Battle over the Durbin Amendment Begins

Now that you have an idea of the main points of the Durbin Amendment, let’s look at the participants in the battle raging over its future, or lack thereof.

The Opposition

On June 14, 2016, Texas Senator Randy Neugebauer fired the first formal shot for the opposition by introducing H.R. 5465, which aims to repeal the Durbin Amendment, and has the official title: To repeal section 1075 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 relating to rules for payment card transactions, and for other purposes.

H.R. 5465 is currently in the introduction phase in the house, but it has already sparked a fierce debate between those for and against the Durbin Amendment.

Senator Neugebauer very eloquently conveyed the feelings of his base by referring to the Durbin Amendment as “an egregious example of the federal government picking winners and losers. Simply put, it represents crony capitalism at its worst.”

On September 9, 2016, Texas Congressman Jeb Hensarling launched another attack on the Durbin Amendment with his introduction of H.R.5983 – the Financial CHOICE Act of 2016.

The Support

On the other side of the Durbin battlefield are retail and industry groups such as RILA and NACS. These groups are backed by hundreds of generally medium to large businesses such as retailers and restaurants – Essentially, businesses with enough resources to understand the complexities of the fees they pay to process credit and debit card transactions.

Those in support of the amendment claim it provides needed protection against anti-free market forces at work in the credit card processing industry. The position of the support is well outlined by similar letters sent to lawmakers on July 11, 2016, and most recently on November 15, 2016.

The battle lines are drawn and they fall pretty much where you’d expect – between the card networks/financial institutions, and larger businesses/industry groups.

Now that we know the players involved, let’s sift through the finger pointing and spin to outline of the main points that each side is using to bolster its argument and respective position in the debate.

Arguments to Repeal Durbin

I’ve outlined the main points of the argument to repeal the Durbin Amendment in the list below. I’ve withheld any opinions or insight for the sake of conveying them with clarity.

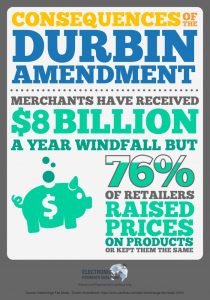

- Retailers are not passing the savings from reduced debit interchange cost on to consumers.

- Durbin is increasing consumer banking costs due to higher charges and vanishing debit card reward programs.

- Regulated (large) banks are no longer offering free checking.

- Regulated (large) banks have stopped offering debit reward programs due to reduced interchange income.

- The number of “unbanked” consumers is increasing due to higher checking account fees and higher minimum balances required to avoid bank fees.

- The amendment has resulted in a large cost to community banks and credit unions to comply with the network routing requirements.

- The debit interchange cap increases costs for businesses with a low average sale amount.

In support of repealing Durbin, groups like the Electronic Payments Coalition publish images like the one below:

Arguments to Uphold Durbin

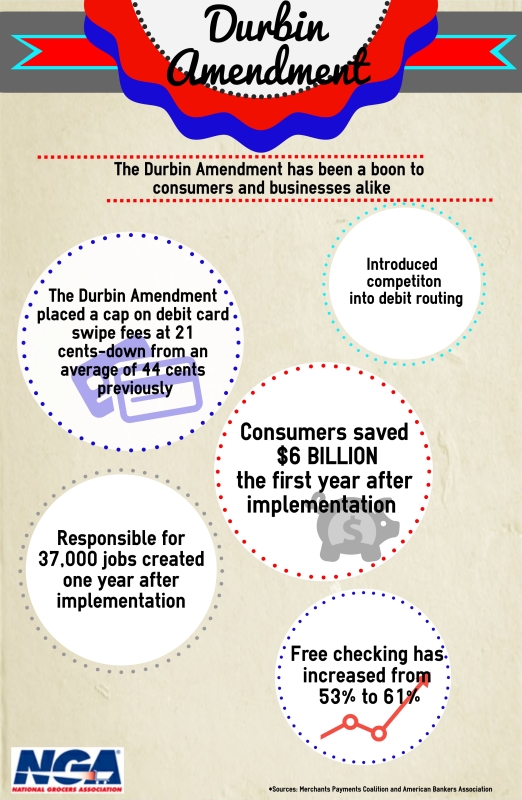

The main points for those in support of Durbin are listed below.

- Without regulation, interchange costs for businesses will rise, the burden of which will be passed to consumers in the form of higher prices.

- Without the amendment, debit network routing will return to the monopoly it was, thereby allowing the card networks to price-fix debit interchange without competition among debit networks.

- Bankcard acceptance in the United States is dominated by global card networks that have failed to move toward a more transparent, equitable, and free market, thereby causing the U.S. to lag behind international payment markets in both competition and innovation.

Groups like the National Grocers’ Association publish their own images, touting the benefits of the Durbin Amendment:

Big Picture: Durbin Missed “Main Street”

The focus of the Durbin debate has been a battle at the top between larger businesses, industry groups, and financial institutions.

For all of their differences, the opposing sides have one thing very much in common. Each has completely lost sight of how the Durbin Amendment’s true impact is felt once it trickles down to real “main street businesses.”

The reality of the amendment’s impact, or lack thereof, is directly related to many of the specific arguments each side makes for its case.

Truth be told — many businesses have never realized a decrease in debit processing expense as a result of the amendment, which makes the entire topic of Durbin a non-issue.

As I’ll explain below, all of the savings businesses are supposedly receiving as a result of the debit interchange cap and competitive routing is actually going into the coffers of merchant service providers (“credit card processors”).

Debit Cap Derailed: Businesses Pay “Merchant Discount”

The term that derails Durbin’s debit interchange cap for many small businesses is merchant discount. As Visa specifically states on its Web site:

“Merchants do not pay interchange reimbursement fees—merchants negotiate and pay a “merchant discount” to their financial institution…”

In other words, Durbin capped interchange, but businesses don’t pay interchange. So essentially, interchange isn’t capped for businesses. It’s capped for merchant service providers with whom businesses must negotiate pricing (merchant discount).

A business’s ability to negotiate pricing dictates whether it or the merchant service provider benefits from lower debit interchange cost.

An overwhelming number of small businesses are hopelessly lost when it comes to the specifics of navigating interchange when it’s run through the myriad pricing models contrived by merchant service providers.

Therefore, businesses are helpless to effectively negotiate merchant discount, and any savings the business would receive from lower debit interchange stays in the pocket of its merchant service provider.

We warned businesses of this issue all the way back in 2011 when the ink was still wet on the amendment, but it received relatively little attention.

An Example of Derailed Debit Interchange

As we explain our processing guide, credit card processors use various pricing models to bill businesses for the cost of processing a transaction.

Unbeknownst to many businesses, the cost of each transaction is made up of three key components: interchange, assessments, and a processing markup. The sum of these components equals “merchant discount.”

More important than the pricing that a processor quotes is the pricing model is uses to pass the cost of merchant discount to a business.

Most processors prefer to use a type of pricing we refer to as “bundled.” Meaning, the processor charges a business one rate and fee and it pays the separate components of cost behind the scenes.

For example, a processor may charge a business 2.25% plus a $0.30 transaction fee. Then, it pays the capped debit interchange of 0.05% plus $0.21 and assessments of 0.13% plus $0.02 from what it collects from the business.

The remaining 2.07% plus $0.07 is the gross markup kept by the processor.

In this scenario, the Durbin debit cap inflates the processor’s markup. It never reaches the business.

Debit Network Routing: A Tough Choice

Very few businesses understand how to use debit network routing to their advantage and many wouldn’t be able to, if they did.

Effectively optimizing (lowering) interchange expense on debit transactions requires an understanding of card network interchange compared to debit network interchange and how the cost for each varies when affected by average sale amount, merchant category code, and more.

Additionally, whether a business can reap the benefits of optimized debit routing depends still on the pricing model its processor is using to assess merchant discount.

Now that I’ve aired some reality on Durbin’s impact on “main street businesses,” let’s take another look at the two key arguments for and against the amendment.

Arguments to Repeal Durbin: Take Two

Argument: Retailers are not passing the savings from reduced debit interchange cost on to consumers.

An overwhelming number of small businesses haven’t received a price reduction to pass along. Most studies that examine this point fail to make a very important distinction, which is if the businesses studied are being assessed merchant discount in such a way that allows them to benefit from the debit cap, or network routing.

In one of the more comprehensive papers on Durbin the authors examine the difference in merchant discount between small and large businesses, and they confirm the ability of large businesses to better negotiate cost post-Durbin.

Arguments to Uphold Durbin: Take Two

Argument: Without regulation, interchange costs for businesses will rise, the burden of which will be passed to consumers in the form of higher prices.

I agree. But as I’ll explain later, I think the Durbin Amendment falls short of making a real dent in interchange as a whole and how its cost is paid by most businesses.

My Two Cents

Knowledge is power, and most businesses are powerless to help themselves or their would-be cause when it comes to navigating processing costs, or even having an opinion to weigh in and get involved in debates that shape the future of such costs, such as the Durbin Amendment.

600 large companies signing a single letter to battle powerful lobbies is a good start, but 600,000 empowered small businesses united behind a cause will go much further to drawing the attention of politicians and the powers that be to rein in runaway interchange and the opaque bankcard industry.

The Durbin Amendment is a good first step toward bringing interchange and the cost associated with processing bankcards out from the shadows, but a more effective approach is needed – one that interjects transparency into the industry as a whole, instead of dictating specific pricing or routing within it.

Interchange is only part of the problem in an industry that is so opaque and unscrupulous that just a basic set of ethical standards in a processor holds value to a business. Even pricing models that claim transparency, or that distort interchange through “merchant discount1” are used as misleading value propositions. The bar is very low.

Businesses should be able to determine the value of a merchant service provider by examining the technology and services it offers, not from gimmicks or an empty promise of fair play.

The power of a fair open market to reward innovation and service through higher profit is forever stuck behind price when businesses that process credit cards are unable to determine even the basic cost of a given service.

As it stands, the foundation for value and margins in the processing industry are built upon a house of cards called interchange.

It’s obvious that some sort of regulation is needed to get the bankcard industry on track, but I don’t think dictating interchange or routing that’s a mystery to most people affected by it is the answer.

Forcing a level of transparency is the answer to empowering the masses.

Hold the financial institutions and card networks that control interchange and routing accountable by simply exposing the real cost of processing to the businesses that pay it.

For example, require merchant service providers to disclose the amount of interchange paid to issuing banks and assessments paid to card brands on a business’s monthly processing statement. The numbers will quickly bring the reality of processing cost into perspective for all small businesses, and processors already have the facilities in place to easily provide such reporting without undue cost.

Businesses can’t get behind a cause they can’t see. Make it a fair fight, and the power of an open market will quickly act to find equilibrium.

Follow us on Facebook or Twitter to stay up to date on the repeal efforts and how your business may be affected.